Highlands Source Project - Regional Drought Relief

In early 2007 a water sustainability taskforce established by the incumbent Premier of NSW recommended the construction of an emergency pipeline from the Wingecarribee Reservoir to Goulburn. Both the Australian Government and NSW Government offered support of up to $20 million each towards the then estimated project cost of $54 million. Our Principal managed this project throughout the planning, design and construction phase. Our Client resolved to levy ratepayers to fund the balance of the project cost. The Australian Government’s contribution came from the Water for the Future - Water Smart Australia Program administered by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPaC). The NSW Government provided funds through the NSW Office of Water. In June 2007 Goulburn’s water supply fell to just 12% of capacity which consisted of less than 12 months supply at restricted levels of demand, however rainfall in mid 2007 partly replenished the city’s water supply. While the immediate urgency to construct a pipeline had diminished, the commitment to secure the city’s water systems remained. Our Client therefore began technical investigations at this time and the development of an Integrated Water Cycle Management (IWCM) Plan to evaluate all available opportunities for the future commenced. The IWCM was completed in early 2010 and confirmed the Highlands Source Project and an expanded demand management program as the preferred long term solution to resolve Goulburn’s water security.

Defining the Scope

The Highlands Source Project ultimately involved the planning, design and delivery of an 81 km pipeline and pumping station between Wingecarribee Reservoir in the NSW southern highlands and the City of Goulburn (population 21,000). The key engineering and other project features included:

- An 81 km Glass Reinforced Plastic (GRP) pipeline. 9 km of 375 mm diameter pipe from Wingecarribee Reservoir to the township of Towrang (sourced from Fibrelogic Pty Ltd in South Australia) and 32 km of 300 mm diameter pipe from Towrang to Goulburn (sourced from Superlit in Turkey). - Mild Steel Concrete Lined (MSCL) pipe, Mild Steel Epoxy Lined (MSEL) pipe and High Density Poly Ethylene (HDPE) pipe were also used through some water crossings where the crossing technique, which was heavily influenced by environmental constraints, determined installation method and the pipe material selection.

- An off-take and pumping station at Wingecarribee Reservoir, near Moss Vale. Initial transfer capacity is 5 million litres of water a day, which can be augmented to an ultimate capacity of 7.5 million litres per day should the need arise in the future.

- The pipeline route was developed with consideration of technical, social, financial and environmental factors. It was installed next to existing infrastructure easements (high pressure gas and fibre optic cabling) to avoid town centres and major roads. The use of an alignment beside existing cleared infrastructure easements resulted in only 11 hectares of vegetation being removed along the entire alignment.

- Seven roads were underbored including an approximate 100 m crossing of the main north – south artery the Hume Highway.

- 15 minor sealed roads and 51 minor unsealed roads were crossed by open trenching methods.

- Five underbored crossings of the main Sydney – Melbourne Railway, Goulburn – Crookwell Railway and the Moss Vale – Unanderra Railway were completed.

- 18 divide valves were installed on the pipeline to allow isolation of sections for maintenance purposes.

- 126 air valves and associated structures were installed at high points along the pipeline to ensure the correct hydraulic performance of the system.

- 115 scour valves and associated structures were installed at low points along the pipeline to facilitate future maintenance.

- 118km of temporary rural fencing was installed to protect livestock during construction. A total of 240 temporary gates and 500 permanent gates were installed to facilitate landowner access during construction and rehabilitation.

- A 40% (19 ha down to 11 ha) reduction in the clearing of native vegetation was achieved through collaborative landowner and contractor discussions.

- 130 waterways were crossed using a range of methods applicable to the crossing location. Whilst a large number of these crossings were ephemeral drainage channels, a number were more significant perennial rivers and creeks.

- The pipeline passed through two local government areas, crossed 145 private properties, crown reserves, numerous public roads, the Sydney-Melbourne tank fibre optic cable owned by AAPT, overhead 33 kVa power transmission lines operated by Transgrid, numerous railways, and traversed a myriad of terrain types and land uses. The pipeline also ran parallel to the Sydney- Moombah gas pipeline operated by APA Group.

Managing Landowner Impacts

While the completion of the project has, and will, result in many social and economic benefits for Goulburn, it was important to recognise the impacts to affected landowners during construction. Affected landowners did not benefit from improved water security as the pipeline route was almost entirely outside Goulburn’s water reticulation network. It was also determined that stock and domestic water supply connections would not be provided to affected landowners. The key approaches taken to reduce these impacts are outlined below. Recognising early on that such a large infrastructure project may result in some unavoidable impacts we developed processes and principles that balanced fairly the benefits and need for the project with the unavoidable impacts to the environment, land and property. An environmental assessment was prepared under Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. The assessment firstly identified potential impacts and then recommended and implemented measures to avoid, minimise or mitigate them. The mitigation measures recommended in the environmental assessment assisted the project team and contractors not only during construction but also beforehand during the planning and design of the project. The team adopted an approach to route selection based on technical merit to reassure landowners that there was a sound justification for the location of the pipeline on their property. Early engagement with landowners during the development of the environmental assessment, and then again during the formal exhibition period, gave the project team a good understanding of the issues that needed to be addressed through either changes in design or by adopting different techniques during the construction and rehabilitation phases of the project. A key concern for many landowners was how the pipeline would be installed on their properties and how the terms for an easement would be negotiated. To help reduce the impact on affected landowners, Council reduced its preferred pipeline easement width from 10 metres to 6 metres. Council thereafter sought to negotiate with landowners to acquire a 6 metre wide easement by amicable agreement and to rent a strip of temporary work space generally 14 metres wide. The approach taken by the project team was proactive with team members providing as much information as possible so that the landowner could make an informed decision. Council encouraged and paid for landowners to obtain independent property valuations undertaken by a valuer of the landowner’s choosing and encouraged and paid for landowners to obtain legal review and advice on the easement agreement. While some landowners initially resisted efforts to negotiate amicable terms, by the end of the project, all but one landowner had signed an easement agreement. Another concern for landowners that was identified during the initial community engagement program was the protection of land and livestock during and after construction. To overcome this, the project team visited each landowner at their property to better understand their specific concerns and requirements. The project team also adopted a science based approach to rehabilitation by carrying out pre-construction agronomy assessments, which were then used to define the required approach to rehabilitation. Landowners were asked to sign a report indicating that they agreed with the construction and rehabilitation approach. The reports, which formed part of the construction contract, were then used as a means by which each landowner could sign off at the end of the project that they were satisfied with the work done by the construction contractor. This approach managed landowner expectations and has assisted Council with its ongoing vegetation and property rehabilitation program.

Delivery Phase

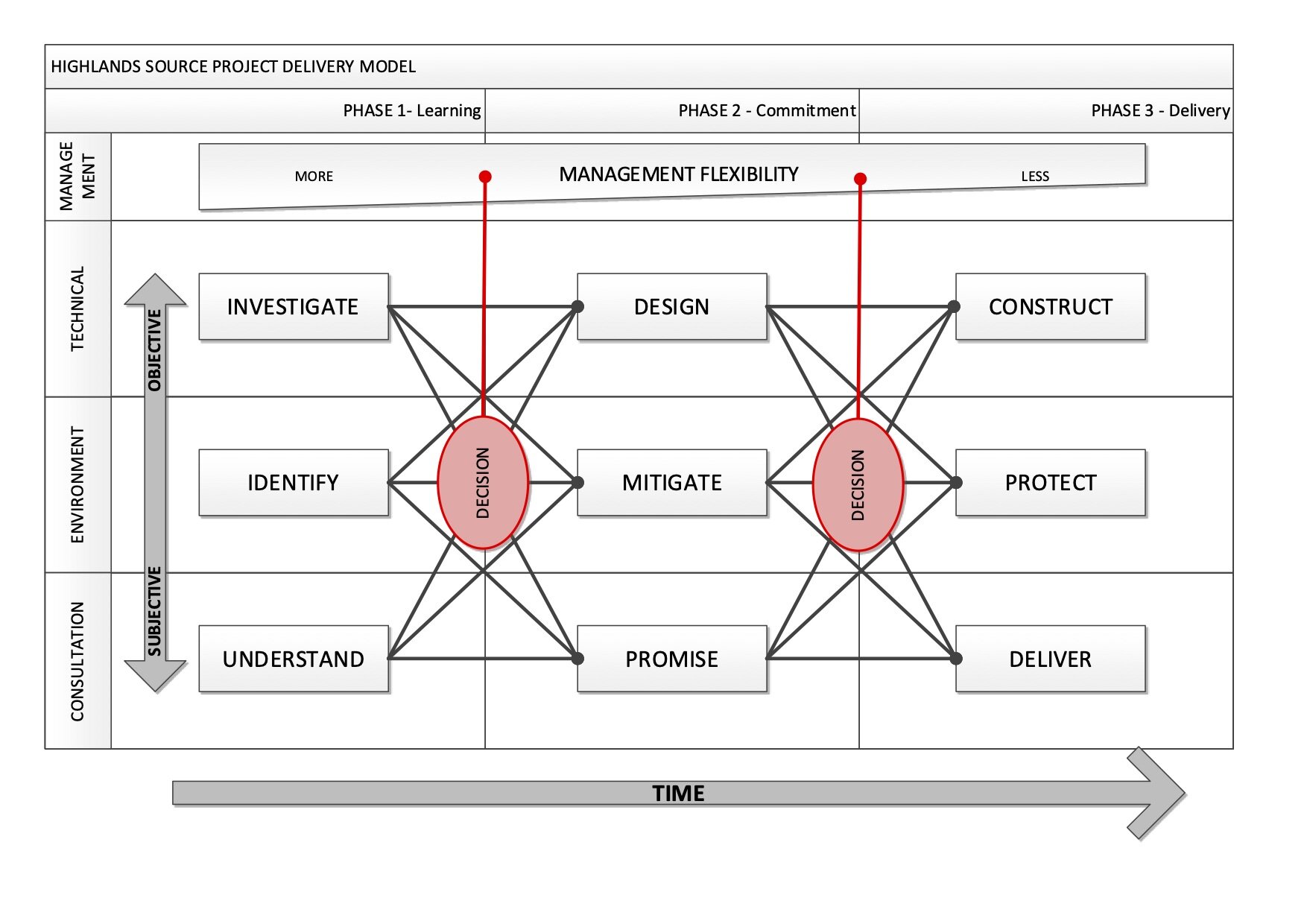

The delivery phase of the project was compressed to a relatively tight timeframe due to the threat of further drought and because the funding agreement with the Commonwealth required that funds be utilised by 30 June 2011. Other, more unique, challenges are outlined in the section below. The project team was able to manage these challenges because of the delivery model, which ensured complex issues were identified early on but managed throughout all stages of the project. The overall commitment to protecting the environment and addressing the concerns of local communities resulted in a much smoother delivery process that minimised delays during construction. The delivery model developed for the project shown below was developed with the advantage of conducting multiple activities in parallel streams. Project delivery was divided into three key task areas: Technical, Environment and Consultation. These proceeded in three phases: Learning, Commitment and Delivery. The Project task areas are summarised below by delivery phase.

Technical

The Technical task area contains the traditional design and construction activities which considers terrain, materials, logistics, resources and engineering design to arrive at a solution. The objective for this task area was to design and construct a pipeline to achieve the required flow condition for the lowest total capital and operating cost. Examples of tasks carried out in this area included:

- Phase 1 - Investigate. Survey, Service Locating, Terrain Assessment

- Phase 2 - Design. Engineering Calculations, Drafting, Contract Preparation

- Phase 3 - Construct. Excavation, Pipe laying, Fencing, Reseeding etc

Environment

The Environment task area contains tasks which consider the impacts of the project on the Environment. The objective for this task area was to minimise environmental impacts to the lowest practicable extent. Examples of tasks carried out in this area included:

- Phase 1 - Identify. Specialist technical investigations to identify the broadest possible range of potential environmental constraints within the project corridor. Specialist disciplines included: Ecology; Archaeology; Visual Impact; Geo- morphology and Aquatic Ecology; Noise; Traffic and Water Quality.

- Phase 2 - Mitigate. During this phase activities focussed on understanding the constraints and evaluating ways to avoid the constraint in the design or mitigate the impact elsewhere.

- Phase 3 - Protect. During this phase the priority was to protect the environment from unanticipated consequences due to construction activity. Work also continued on minimising actual impacts by refining construction methodologies to suit actual conditions at the time of construction.

Consultation

The Consultation task area contains tasks which consider the impacts of the project upon the community such as: affected landowners; the general public; affected service authorities and other government agencies.

- Phase 1 - Understand. A series of meetings and discussions were held with as many members of the community as possible in order to gain an understanding of as many real and perceived concerns related to the project as possible.

- Phase 2 - Promise. During this phase, activities focussed on developing and implementing a framework to allow the project to commit to things that would or wouldn’t be allowed to occur in relation to affected land or other assets.

- Phase 3 - Deliver. During this phase the priority was to monitor and deliver on the commitments made in the earlier phases.

Highlands Source Project Delivery Model

Complex decision making

It became clear that activities within each task area and phase were all interlinked and dependent upon each other in some form. For example; decisions concerning the space required for construction would affect the amount of vegetation to be cleared and the level of impact on farming activities. Avoiding an environmental constraint might increase the risk of damaging underground services. The arrangement of existing fences may cause impacts to a much larger proportion of an individual property than a similar adjacent property. Commitments made to landowners may impose significant constraints on construction methods. Decision making during the project required an evaluation of the impacts against all task areas and ultimately an assessment of the relative importance of the issue in relation to the project delivery. Complexity of the decision making was increased by the relative subjectivity of the task areas - with technical tasks being the least subjective, environmental tasks being partly subjective and consultation tasks being almost entirely subjective. To assist in Project Management decision making, we developed a set of values and principles which could be expressed as a Project Conscience; the idea that every decision should be fair and reasonable and did not impose impacts and restrictions on the community which were greater than the benefits the project could provide. The Project was completed in 2011 and was delivered on time and within budget, exceeding the expectations of the community and Government. It provides a benchmark against which other regional drought relief projects can be judged; providing an example for how urgent drought relief works do not necessarily have to unfairly impact affected sections of the community or the environment. Industry recognition came with an Engineering Excellence award in 2012 in the Engineering for Regional Communities Category.

Get in touch to find out more about how our insights could benefit decision making in your next infrastructure project.